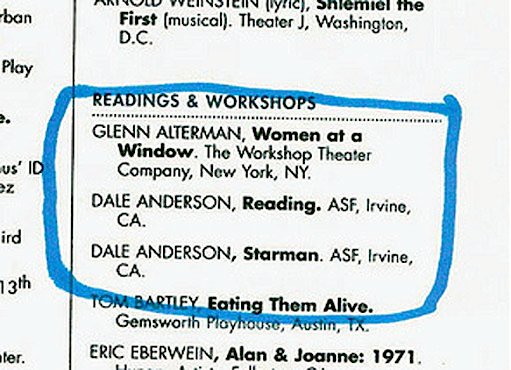

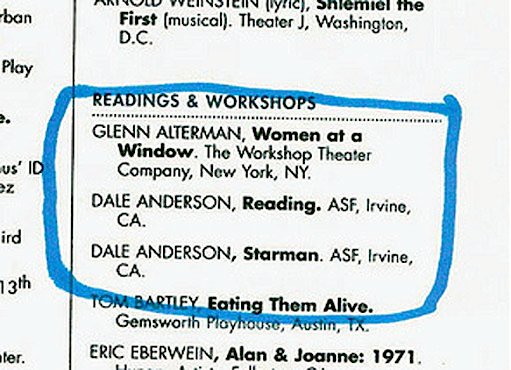

An ego-booster yesterday. The Spring issue of The Dramatist arrived and there I am, mentioned not once, but twice. Misspelled, of course. If your name's Andersen, everyone west of Denmark writes you (off) as "Anderson." Like the Strother Martin character says in Butch Cassidy, "Morons. I've got morons on my team."

The reason for my being mentioned was a reading of my Starman monologue on December the fifth at ASF. Thanks to Alan Witchey, by the way, for providing the venue and the support (chairs, snacks, etc). I got lucky at ASF, because one of my favorite actors, Michael Csoppenszky, read. Michael is unbelievable when he's in his zone. Very edgy, very intense, a little scary. I get chills watching Michael work. I always know when I'm in the presence of a really good actor. My chills act up. For those of you who've never experienced Michael, this is what he looks like:

Starman's been good to me. I wrote it on a train. I was on AMTRAK going up to Alaska for Edward Albee's Last Frontier Theatre Conference in 2004 and I read that Pete Knight had just died. Pete Knight was a famous fighter jock who set speed and altitude records. He retired and turned to politics. The California homosexual community remembers him unfondly as the author of Proposition 22.

It gets better. And it's the kind of story you could not make up in a hundred years. Only one of Pete's six kids followed him into the Air Force. David. David became a fighter jock and flew combat missions during Operation Desert Storm. When David left the Air Force, he publically announced that he was a homosexual and wrote an op/ed piece in opposition to Prop 22.

I imagined a scene with David returning home for the funeral. I imagined some moments alone in the viewing room. And I tried to imagine what he would say, And I wrote that.

Starman got productions at FirstStage up in Hollywood (it shared the bill with Edward Asner) and at some off-Broadway venues. Not bad for ten minutes' work on a train.

Okay. Enough! Here is Starman:

(A viewing room at a funeral home. An open coffin,

subdued lighting. Enter DAVID, age 44. He

approaches coffin with trepidation. He comes

to at ease by degrees. Finally.........)

So. Here we are. Finally. And I guess I should be happy. But I'm not. And I guess I should feel a sense of release. But I don't. I take no pleasure in seeing you this way. I feel no joy in witnessing your departure from this level of existence. It consumes a part of me that we never were able to come to terms. We should have been able to move past the differences. We should have been able to live and let live. This I know. There's no winning and there's no losing in concerns of family blood. It matters not a whit who fired the first shot. No one remembers anyway. But once the knives are out, once there's the smell the blood, it's father against son, son against father, the old king against his heir, and hard words all around.

You're damn right I blame you. You know how the media loves a good fight. And you know how easy it is to manipulate them. And you know how to craft a tight sound bite. What was you told them? "We love Davey. But we don't love what he's become." Why am I still Davey? I'm forty-four. And who is this we person?

I had a dream. I was four. I mean, in the dream I was four. I must have been sixteen or seventeen when I was having the dream. I'm not exactly sure. After all, this is from nearly thirty years ago. We're in a single-engine Beech. Just you and I. We take off from Hammer Field in Fresno and we're somewhere out over the Coast Range. The engine starts kicking in and out. The smell of burning oil. You shout, I'm taking her down, Davey. We break through the cloud cover. There was black smoke in the cockpit. You point to a stream below. If I don't make it, follow the flow of the stream. You hear me, Davey? Follow the stream. I'm crying, Okay, Dad. I promise. Just leave me, Davey. If it's my time, nothing you can do. If it's not, they'll send a search party. I can hear you laughing. You're working the controls, You're muttering, "Okay Pete, show me what you got."

I hated that dream. I buried it deep. My psychiatrist said I repressed it. Well, of course I did. It needed repressing. Deserved repressing. I don't need to be reminded that my being close to you entails my being scorched in your sun. That's how you see us, isn't it? All of us in orbit around you. Except for those who found a way to break free of your gravity.

Another dream. We're in a car. You and I. And you're driving me to prison. It wasn't clear why I was going to prison. But there I was, sitting next to you on the passenger side. Neither of us speaking. The road running across a flat featureless landscape. We stop at a railroad track to let a train pass. Then we drive on into the night. My psychiatrist wondered if, while the car was stopped, had I tried to run away, would you have tried to stop me. I told him no. I said you would have let me go. I lied.

Another lie. Joseph and I living our lives together invisibly. Just out of your reach. Just under your radar. Hoping someday you'll change. Or, if not change, then die quietly, letting things sort themselves out naturally.

I never wanted to be a poster boy. I never wanted to fight you. But, regardless of what you kept saying, that Defense of Marriage Act you promoted reaches beyond the grave. And that is wrong. It is one thing for the old to dictate to the young. It is quite another for the dead to dictate to the living. And that's what you intended. When that thing became law, you had your house set in order, so that you could leave and nothing would change. Like a pharoah in a pyramid.

So in the end, we fired our guns. No direct hits. But I did some nice stitching on your fuselage and you, on mine. You said of me, "I love Davey, but we continue to disagree. And because this is a private issue, I do not wish to respond further." Every pause, every tilt of the head, every clearing of the throat. All too perfect. All too practiced. There was nothing private. It was public. It was political. And you intended it so. The Lambda people called me every day. Make a statement, they said. Make a statement, David. They called me David. Someone finally called me David. I said of you, "His is a blind, uncaring, uninformed, knee-jerk reaction to a subject about which he knows nothing and wants to know nothing." You deserved that. Because you used me.

Finally, in my mind, I went back to the crash site. The smashed single-engine Beech. I saw dried blood on the pilot's seat. The pilot-side door was kicked open. And ten feet away, I saw an old weathered glove on the ground. The glove fit a man's hand. And inside the cockpit, I saw parts of a little boy's skeleton. Some of the bones were missing. Rats and coyotes, no doubt. It told me what I already suspected. Davey died in that crash. And there hasn't been a Davey for a long, long time.

But there's a David. And he's alive. And he's doing okay.

Farewell, starman. Godspeed.

(Salutes. Blackout)

The reason for my being mentioned was a reading of my Starman monologue on December the fifth at ASF. Thanks to Alan Witchey, by the way, for providing the venue and the support (chairs, snacks, etc). I got lucky at ASF, because one of my favorite actors, Michael Csoppenszky, read. Michael is unbelievable when he's in his zone. Very edgy, very intense, a little scary. I get chills watching Michael work. I always know when I'm in the presence of a really good actor. My chills act up. For those of you who've never experienced Michael, this is what he looks like:

Starman's been good to me. I wrote it on a train. I was on AMTRAK going up to Alaska for Edward Albee's Last Frontier Theatre Conference in 2004 and I read that Pete Knight had just died. Pete Knight was a famous fighter jock who set speed and altitude records. He retired and turned to politics. The California homosexual community remembers him unfondly as the author of Proposition 22.

It gets better. And it's the kind of story you could not make up in a hundred years. Only one of Pete's six kids followed him into the Air Force. David. David became a fighter jock and flew combat missions during Operation Desert Storm. When David left the Air Force, he publically announced that he was a homosexual and wrote an op/ed piece in opposition to Prop 22.

I imagined a scene with David returning home for the funeral. I imagined some moments alone in the viewing room. And I tried to imagine what he would say, And I wrote that.

Starman got productions at FirstStage up in Hollywood (it shared the bill with Edward Asner) and at some off-Broadway venues. Not bad for ten minutes' work on a train.

Okay. Enough! Here is Starman:

STARMAN

A monologue

By

Dale Andersen

©2005

Synopsis

A powerful man, who in life was a prominent politician, gaybasher and war hero, is dead. His gay son, long estranged, has come home to pay his respects and heal. Based on a true story.A monologue

By

Dale Andersen

©2005

Synopsis

Character Breakdown

DAVID.......................early 40s

Technical Requirements

A coffin, subdued lighting

(A viewing room at a funeral home. An open coffin,

subdued lighting. Enter DAVID, age 44. He

approaches coffin with trepidation. He comes

to at ease by degrees. Finally.........)

DAVID:

Well. Well well. Just look at you. All decked out in your astronaut's garb. Dressed to kill, aren't you? Was this how you planned it? To do your exit as a starman? It does become you, you know. Really, it does. So tell me, are you braced for tomorrow? Have you dialed in your humble mode? You know they'll be sending you out as only the Air Force can. Full military honors. A flyover with the missing wingman. And they'll retell how one time you flew so high, you tweaked the chinwhiskers of Zeus himself. And they'll retell how you throttled that demon out at mach seven. Yes yes, I know it's all true, but remember, the order of the day is humility. They'll want to see your aw shucks side. Not funny? Sorry. I'm trying to be clever. Guess I'm not very good at clever.So. Here we are. Finally. And I guess I should be happy. But I'm not. And I guess I should feel a sense of release. But I don't. I take no pleasure in seeing you this way. I feel no joy in witnessing your departure from this level of existence. It consumes a part of me that we never were able to come to terms. We should have been able to move past the differences. We should have been able to live and let live. This I know. There's no winning and there's no losing in concerns of family blood. It matters not a whit who fired the first shot. No one remembers anyway. But once the knives are out, once there's the smell the blood, it's father against son, son against father, the old king against his heir, and hard words all around.

You're damn right I blame you. You know how the media loves a good fight. And you know how easy it is to manipulate them. And you know how to craft a tight sound bite. What was you told them? "We love Davey. But we don't love what he's become." Why am I still Davey? I'm forty-four. And who is this we person?

I had a dream. I was four. I mean, in the dream I was four. I must have been sixteen or seventeen when I was having the dream. I'm not exactly sure. After all, this is from nearly thirty years ago. We're in a single-engine Beech. Just you and I. We take off from Hammer Field in Fresno and we're somewhere out over the Coast Range. The engine starts kicking in and out. The smell of burning oil. You shout, I'm taking her down, Davey. We break through the cloud cover. There was black smoke in the cockpit. You point to a stream below. If I don't make it, follow the flow of the stream. You hear me, Davey? Follow the stream. I'm crying, Okay, Dad. I promise. Just leave me, Davey. If it's my time, nothing you can do. If it's not, they'll send a search party. I can hear you laughing. You're working the controls, You're muttering, "Okay Pete, show me what you got."

I hated that dream. I buried it deep. My psychiatrist said I repressed it. Well, of course I did. It needed repressing. Deserved repressing. I don't need to be reminded that my being close to you entails my being scorched in your sun. That's how you see us, isn't it? All of us in orbit around you. Except for those who found a way to break free of your gravity.

Another dream. We're in a car. You and I. And you're driving me to prison. It wasn't clear why I was going to prison. But there I was, sitting next to you on the passenger side. Neither of us speaking. The road running across a flat featureless landscape. We stop at a railroad track to let a train pass. Then we drive on into the night. My psychiatrist wondered if, while the car was stopped, had I tried to run away, would you have tried to stop me. I told him no. I said you would have let me go. I lied.

Another lie. Joseph and I living our lives together invisibly. Just out of your reach. Just under your radar. Hoping someday you'll change. Or, if not change, then die quietly, letting things sort themselves out naturally.

I never wanted to be a poster boy. I never wanted to fight you. But, regardless of what you kept saying, that Defense of Marriage Act you promoted reaches beyond the grave. And that is wrong. It is one thing for the old to dictate to the young. It is quite another for the dead to dictate to the living. And that's what you intended. When that thing became law, you had your house set in order, so that you could leave and nothing would change. Like a pharoah in a pyramid.

So in the end, we fired our guns. No direct hits. But I did some nice stitching on your fuselage and you, on mine. You said of me, "I love Davey, but we continue to disagree. And because this is a private issue, I do not wish to respond further." Every pause, every tilt of the head, every clearing of the throat. All too perfect. All too practiced. There was nothing private. It was public. It was political. And you intended it so. The Lambda people called me every day. Make a statement, they said. Make a statement, David. They called me David. Someone finally called me David. I said of you, "His is a blind, uncaring, uninformed, knee-jerk reaction to a subject about which he knows nothing and wants to know nothing." You deserved that. Because you used me.

Finally, in my mind, I went back to the crash site. The smashed single-engine Beech. I saw dried blood on the pilot's seat. The pilot-side door was kicked open. And ten feet away, I saw an old weathered glove on the ground. The glove fit a man's hand. And inside the cockpit, I saw parts of a little boy's skeleton. Some of the bones were missing. Rats and coyotes, no doubt. It told me what I already suspected. Davey died in that crash. And there hasn't been a Davey for a long, long time.

But there's a David. And he's alive. And he's doing okay.

Farewell, starman. Godspeed.

(Salutes. Blackout)

End of Play

No comments:

Post a Comment